Context and artifacts

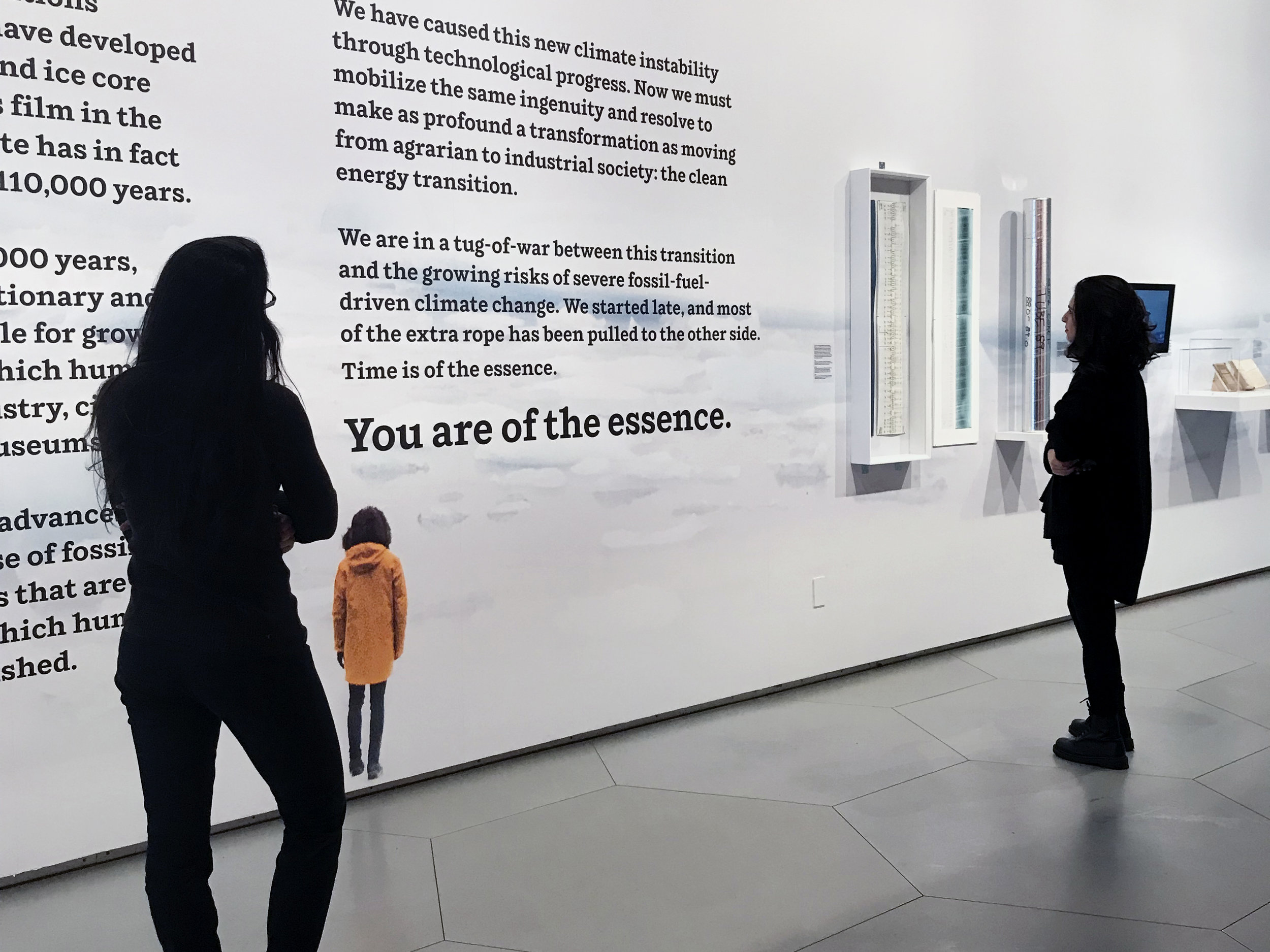

You are of the essence

88 Cores was accompanied in the hallway outside the gallery by artifacts and media offering background on ice core science and the Arctic. Bold messaging on the wall situated Weil's film in the context of ice core science, climate change, and a call for action. Keep scrolling to learn more.

Left: Notebooks annotated by Christopher Shuman, a University of Maryland researcher currently working at NASA’s Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory.

Middle: An image of the ice core at 2128 meters below the surface, together with its page annotations by Tony Gow, formerly of the U.S. Army’s Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory.

Right: A canister used to ship harvested ice core sections under heavy refrigeration to the National Ice Core Laboratory in Denver, Colorado.

Ice core science in action

Ice core science exemplifies the will and talent humans can mobilize in the search for knowledge. The second Greenland Ice Sheet Project yielded a 3051 meter-long ice core, featured in the film 88 Cores. The core provides us with a uniquely clear record of climate conditions over the last 110,000 years. Scientists annotated each meter-long ice core section using custom-made notebooks, a technique used alongside high-technology tools in the field and the lab.

Learn more about ice cores on our Resources page.

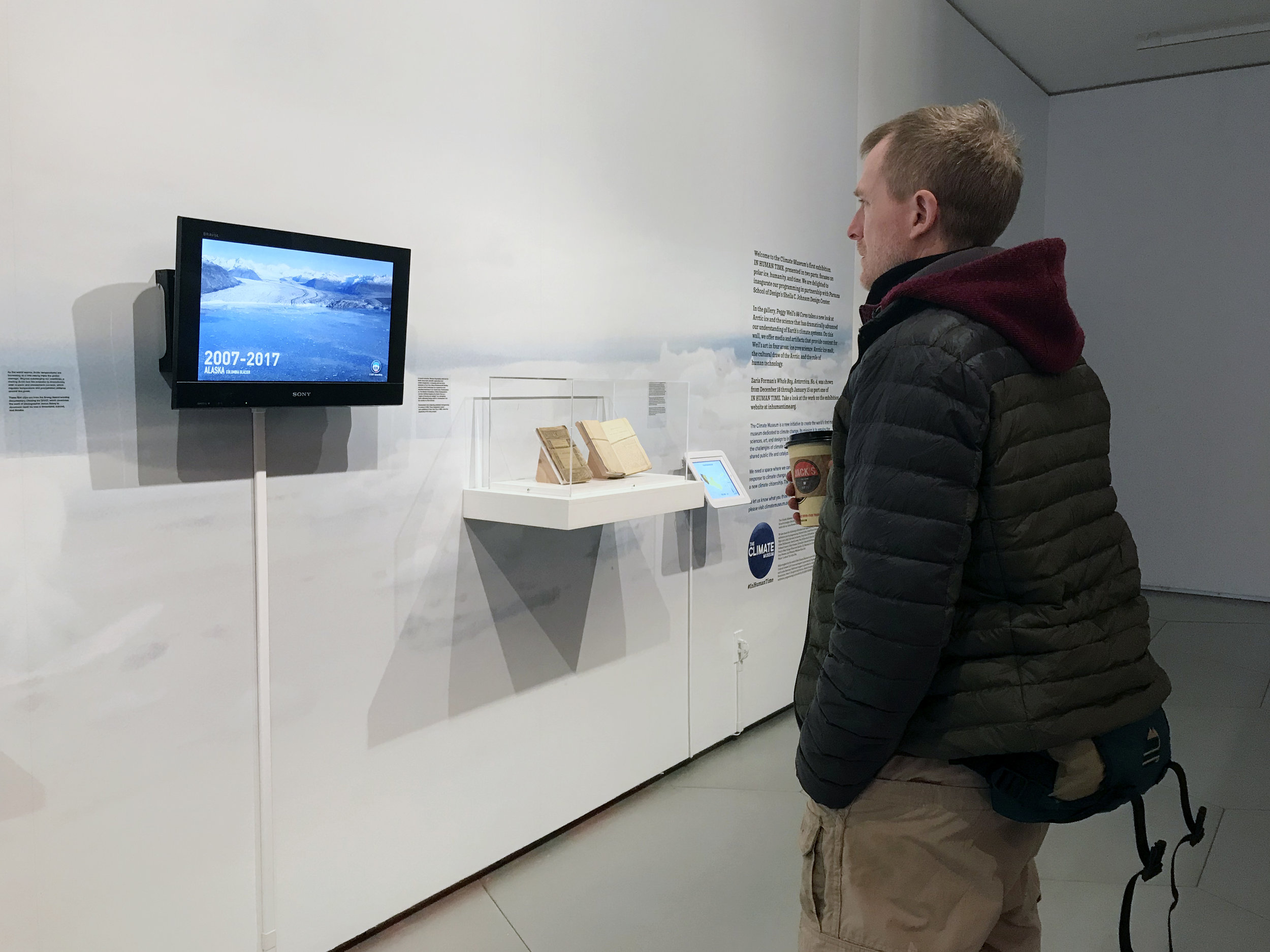

These film clips are from the Emmy Award-winning documentary Chasing Ice (2012), which chronicles the work of photographer James Balog to document rapid ice loss in Greenland, Iceland, and Alaska.

Melting Arctic landscapes

As the world warms, Arctic temperatures are increasing at a rate nearly triple the global average. Beyond submerging our coastlines, a melting Arctic has the potential to dramatically alter oceanic and atmospheric currents, which regulate temperature and precipitation patterns around the globe.

Frankenstein was originally published anonymously in London in 1818. These inexpensive copies were published in New York City in 1882, when the popularity of the story surged.

The Arctic in Western cultures

Western fascination with the Far North in recent centuries drove both scientific exploration and artistic imagination. In keeping with the Arctic obsession of her time, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley uses the Arctic landscape as a mysterious and merciless backdrop in her classic tale, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. While Frankenstein’s narrator initially imagines the North Pole as a “region of beauty and delight,” the unforgiving Arctic ultimately brings both Dr. Frankenstein and his creation to their demise.

This temperature spiral shows Earth’s overall warming since 1850, with impacts to date on the Arctic and around the globe. The maps show how energy generation from renewables has expanded across the United States.

Temperature animation by Ed Hawkins, National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading; map animations by the Natural Resources Defense Council, based on U.S. Energy Information Administration data.

Rising temperatures and the clean energy revolution

While our use of fossil fuels has yielded enormous progress and growth, it has also brought great ecological and social destruction. If greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere continue to intensify, the consequences will be far-reaching and severe. Clean energy has the potential to power more evenly-distributed global development with significant ecological, health, and social benefits.

Why do we need a climate museum?

We asked people at street fairs, at conferences, and on social media why they believe we need a climate museum. We included their answers in a short video we projected on the back wall of the exhibition hallway.

Credit: Arash Fewzee, Sari Goodfriend, and the Climate Museum